The ambition vacuum: inevitability and cultural malaise

Ambition depends on shared stories about the future. The old stories have collapsed, leaving a vacuum of inevitability and futility, especially around AI, the climate, and democracy.

“We’re a pack of bloody whingers!” I exploded in frustration, chatting to my friend Stephen at the end of an interview for The Busker Principle article two weeks ago. “Like, I get it, things are hard, but where’s the fire? Where’s the get up and go?”

It gets worse. “Don’t tell me you’ve ‘burnt out!’ You’re up to Fuck. All. If you were doing something you felt excited about, you wouldn’t be so ‘burnt out!’ (air-quote fingers were used here.) “Maybe get off your ass and try something new for a change?” I fumed. “That’ll be the next piece I write, actually. It’ll just say: get off your ass!”

I mean… Gosh. First, I apologise on behalf of that frustrated, sanctimonious woman. She was a specimen of health, trotting her high horse around the drizzly Pauatahanui inlet, brimming with vim and self-righteousness. (The woman writing this piece, in contrast, is on day nine of the flu and hardly remembers that robust firecracker, who was so quick to judge her fellow countrywomen and men.)

Sanctimony is short-sighted (but reassuring)

The stomping-around-the-inlet-in-frustration woman shares some characteristics with New Zealand’s Prime Minister, actually. He turned up in Rotorua last week, glanced at rocketing youth unemployment and instructed unemployed school leavers to “get off the couch, stop playing PlayStation and go find a job.”

Faced with a worrying trend, both Lady High Horse and Lord Playstation have resorted to blaming individuals, (aka the people suffering the consequences), rather than looking to structural, economic or social phenomena. This approach gifts the finger-pointer (and all those who identify with the finger-pointer) the moral high ground, and boils the problem down to a handy little ball of blame. The lesson: everything is fine, all the choices we’ve made are fine, and a few shit people are just being shit. Can’t touch me, ‘cos I’m not shit like them. What a pleasantly reductive and reassuring way to view the world.

But people (even Prime Ministers) are rarely the problem. They usually behave exactly the way their environment encourages. To understand the anatomy of an issue, we have to look wider - and when we’re looking at population or generation level trends, we have to look far wider.

We’re in an ambition recession

Lady High Horse and and Lord Playstation are right on one count: there is a noticeable cultural swing away from ambition. But the size of the frame is wrong. It’s not just Kiwis suffering this malaise, and it’s not a crisis of individual willpower.

We’re in an ambition recession. It’s a pattern I see everywhere - from political short-termism and managerial risk-aversion, to widespread cynicism in popular entertainment. l speak to hundreds of executives, bureaucrats and politicians every year, and the last few years are the flattest I’ve seen in my career. It’s as if a collective fire has gone out. Politicians who are so captured by social media they won’t invest in vital infrastructure. Workers living in constant fear of restructure and redundancy, who spend their energy flying below the radar, avoiding anything that looks like a new idea. My Gen Z kids trading nihilistic memes while the algorithm manufactures 2000s nostalgia to get them rocking the Y2K aesthetic, (which makes no sense because low-rise jeans didn’t look good the first time.)

The metanarratives are shifting

I’ve been writing a series on the ambition recession, from a range of sniffpoints, ever since I walked out of a conference a few months ago to film this rant in my car. We’ve looked at Poppy Loppers, the insidious cultural programming keeping us feeling and playing small. We’ve railed against the way ambition is discouraged and punished in women, with the P-tax. We’ve explored The Busker Principle, a narrow and outdated understanding of valuable work that undermines our social fabric and future economic engine.

But this all pokes the edges of a bigger puzzle. Ambition is nothing more than a story we tell about what’s possible. And those stories rest on larger cultural frameworks - metanarratives - that shape how entire societies view the world.

Every day, our choices say something about how we understand the world - the stories we believe about good and bad, right and wrong, cause and effect, options and consequences. These stories shape our idea of what’s possible, probable and preferable - and many of them were coded so early, or at such a large scale, that we can’t even see them. They’re the air we breathe, the water we swim in.

And right now, those metanarratives are shifting.

The end of something, the start of nothing else (yet)

We talk about ‘late-stage capitalism’ (or, my preference, ‘last-gasp patriarchy’) in a way that acknowledges the end of something. But the lack of an ‘early-stage’ equivalent suggests we’re not sure what might come next.

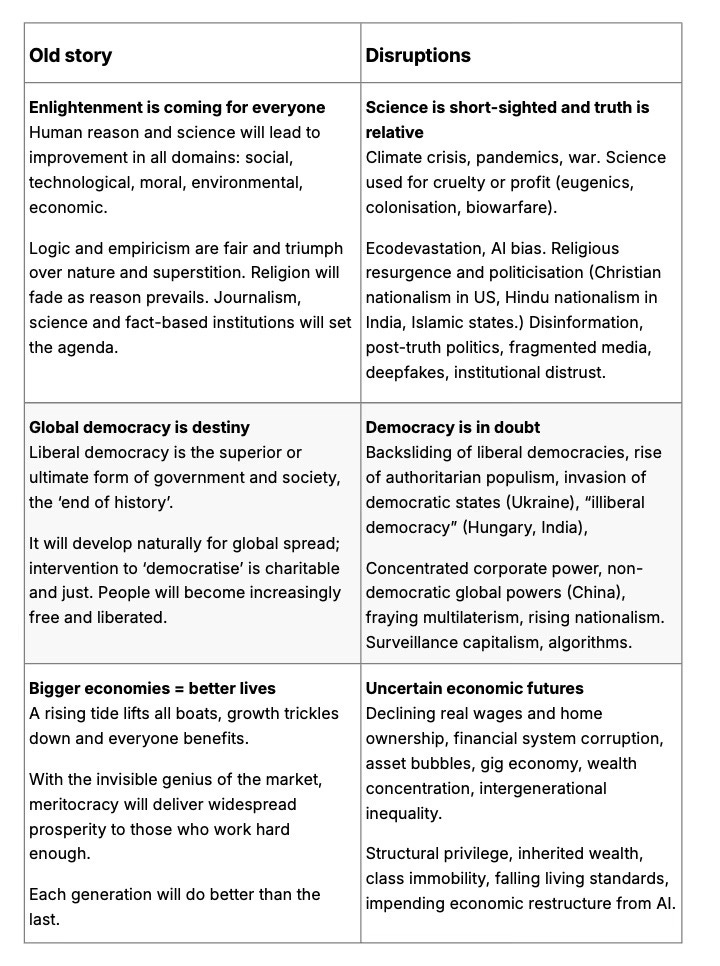

The OG metanarratives of modernity (things like progress, emancipation, science-as-truth) were uniting, totalising forces. Without them, we splinter into bitter little pockets of doubt and detachment, with nothing to believe in.

The table below spells out some of the “old stories” and how these are being undermined or disrupted.

A third column is forming as we speak, bursting with options. A new world will, eventually, prevail. Humans are resilient and have overcome worse moments in history than this. In the meantime, while we’re not sure what comes next, the cultural mood is a collective… shrug. Enter: inevitability.

In the gap, we’ve grown weary

I believe we have a cultural current of inevitability and, ultimately, futility. The Go-Get-‘Em-Tiger ethos of previous decades is hopelessly naive in the face of *gestures broadly*, so we need weary pragmatism and ironic detachment to survive.

In the 90s, we thought recycling would save us, now we drop our rinsed bottles in the bin with a sneer, “Glad I ‘ve seperated these just so they can all end up in the same pile.” We’ve seen the greenwashing and watched decades of politicians across the spectrum fail to meet the call on climate change. The environmental disaffection has been here for a while and the same vibe has spread to technology: especially AI.

AI debates seem to contain three main schools of thought:

Techno-optimists: Get on board, kids! The future is here, and it’s going to free us all! (These people are usually selling AI, or something connected to it.)

Doomsdayers: AI is an existential threat. Sentient robots, autonomous weapons or mass unemployment (or a combo) will end us. (Many leading academics and researchers have now joined this camp.)

Weary pragmatists: Could go either way, but there’s nothing we can do. We have to adapt, because nobody will save us, no matter how bad it gets.

That final category is where the inevitability narrative is strongest. Despite AI’s infancy, and the recency of inventions like smartphones and social media, we have already thrown our hands in the air.

“Like it or not,” people say “It’s not going anywhere, so we’ll have to teach the kids to adapt.” I’m puzzled and impressed at the prevalence of this thinking. Tech companies have told such powerful inevitability stories that people won’t even try to resist, and fear of “falling behind” in some unspoken race does the rest.

As a result, we treat these inventions as though they’re embedded and eternal, aware of how impotent our politicians are before multi-national tech companies. We’re like children with neglectful parents, detaching from our feelings, eliminating all our expectations, in a bleak collective response.

Because we do need something. The function of metanarratives is to legitimise institutions, knowledge and power. When the big stories break down, new ideas emerge to paper over the cracks. According to Frederic Jameson, the cultural logic of capitalism is the ultimate crack-papering PVA. Inevitability fits the bill perfectly - if there’s nothing we can do, may as well party (scroll, and purchase) while the world burns!

Why do things feel so futile?

Things aren’t great, I’ll give you that. The fascists are back, children are committing suicide over deepfakes, and the planet’s careening toward climate collapse.

But the world has always been a manifestly unjust shit heap filled with militant fuckwits tearing societies apart and plundering natural resources. The main difference is that until extremely recently, there wasn’t such widespread consumption of bad news. We didn’t know how bad things were, and we had positive news to balance out the despair.

For most of history, news was local - and it was both finite, and time-boxed. Popular media was more ‘entertainment’ and less ‘terror-inducing true crime’. People consumed a tiny fraction of the information streaming into their eyeballs today, and while newspapers always aimed for attention-grabbing headlines, they didn’t have the technology for such personalised ragebait. Staying informed was an option, not a civic duty or moral calling, and you consumed largely the same information as everyone else.

TV shows and movies - just a few, all played to millions - reinforced the classic metanarratives: the little guy triumphing over the rich villain, bigots examining their prejudices and making social progress, inventors and risk-takers moving the world forward.

Now, when people turn on their medium-sized screens after a busy five hours a day of doom-scrolling their bespoke, infinite, newsfeeds, they choose between the violent dystopia of Squid Game and the bleak, jaded irony of Succession or Severance, else they head to the past for some comfort nostalgia like Friends or The Office, made at a time when we still thought things might get better. Our brains, hijacked by dopamine loops and pickled in the acid of social media, see futility and decline where-ever we look.

Stories - the ones on your social feed and in Netflix - don’t just describe reality, they produce it. Barry Schwartz calls this ‘idea technology’ - the stories we tell about human nature that have the power to change human nature.

If we understand birth defects as acts of God, we pray. If we understand them as acts of chance, we grit our teeth and roll the dice. If we understand them as the product of prenatal neglect, we take better care of pregnant women.”

-Barry Schwartz

At other points in history, rampant corporate greed might have provoked a neo-socialist revolution, collective action, or other resistance. But in a world where where people are physically isolated, socially disconnected and algorithmically polarised, we end up with existential malaise.

The narrative of inevitability, then, is a cultural force with consequences. When we see things as inevitable, we shrink. We perpetuate our own cycle of futility. Which leaves room for the taking, doesn’t it?

The ambition vacuum

Let’s call this what it is: a particularly left-wing problem. There are plenty of people and organisations who profit and power-grab in the current environment. They tend to be those who either:

Directly benefit from the inevitability narrative (technology companies, ecodestroyers) or

Subscribe to a core belief that still aligns with the old stories of progress, reason, and merit (evangelical Christians, conservative politicians, centre-right populist movements with a bent toward nostalgia.)

The futilism of the left creates a vacuum for trad-wives, prompt engineers and militant fascists. It leaves space for the people turning your Nanna MAGA on Facebook and stoking anti-immigration rallies in countries founded on colonisation and post-war immigrants.

It’s easy to write this off as influencers and inches. But the TikTok tradwife empires aren’t just making a fortune shilling aprons and vitamin supplements. They’re encouraging a generation of history’s most liberated women to turn their backs on feminism at a time when those rights are being eroded in countries around the world.

We might be disconnected from our neighbours, but global disinformation networks mobilise with extraordinary real-life results. In 2022, a heady combination of Russian-generated disinformation about COVID-19 vaccines, US-based funding and a handful of ambitious anti-government figureheads whipped farmers and concerned citizens across New Zealand into a convoy frenzy resulting in a three-week occupation of Parliament grounds. Ambition is alive and well on the reactionary right, and it is funded, organised, and loud.

The ambition recession might not be a recession at all, but a redistribution - from the collective to the individual, nation-state to technology company, democratic to autocratic, left to right.

Inevitability is not inevitable

The power of stories are their own kryptonite. We decide things are futile, and they become so. But if we decide they aren’t futile, well, they won’t be. If we reject inevitability - environmental collapse and tech dystopia both - and demand regulation and resistance, the stories can shift - and the future along with it. Cultural narratives are fickle and narratives can be rewritten.

And who’s to say I’m right? This is the beauty of stories. What I see as a key cultural moment, a narrative of inevitability enabling corporate greed and hastening the erosion of democracy, might not be that at all.

Maybe this moment isn’t one of recession at all, but of redefinition. A Gen Z reframe that’s less about work, and more about values. Maybe ambition is alive and well, but it’s retreated into the personal sphere where it’s less culturally obvious. People creating ‘soft lives,’ replete with rich and rewarding relationships, hobbies, gardens and crafts.

Or maybe ambition has migrated into new forms that aren’t visible to an elder millennial who avoid social media. Hustle culture is thrives on the right and in the self-branded influencer world. So that’s less of a recession, and more of a shift away from complaining old people and toward a new economy I don’t understand.

These stories, and 100 others, are all possibilities.

Staring out at the inlet with a pile of snotty tissues, I’m no clearer than you about what the real story is, or if there is one. But the old ones, the narratives that fuelled colonialism, justified extractive capitalism and co-signed tech-driven destruction, are probably due for an update anyway.

Very little is inevitable and things are probably never as bad as they seem on the internet.

blows nose introspectively

-AM

🎶 Soundtrack

I’m knee-deep in a new body of work around power literacy - how to see, work with, and shape the invisible mechanisms of power. New projects require appropriate soundtracks - here’s what I wrote this article to.

Start with this banger: Know Your Enemy by Rage Against the Machine

✍️ Notes

This is all so culturally relative. Sweeping statements about the grand narratives of modernity and their collapse are, like most historical accounts, wildly Eurocentric and leave out almost everything that wasn’t the domain of rich white dudes. They miss out entire continents, genders and frameworks of knowledge. I’m shouting from a protective little bubble, a middle-class white woman in a safe country, cosied close to the powerful with my notebook and my annoying questions. My prickly edges - working-class beginnings, experiences in state care, life as an emancipated child and teen mother - are, in any real analysis, still so close to the mean as to be a rounding error. I have no authority to speak on behalf of the vulnerable or dispossessed, nor to comment on the dominant cultural narratives in any other world than the one I inhabit. This is true for all of us. It’s worth bearing that in mind when reading any cultural or social commentary - or indeed, history book.